Hello, my name is Sibu. And, by and large, I was raised by a television.

It wasn’t by design, or through any mode of logic; it was mere happenstance. My parents worked often, and so I spent much of my time in front of the television, hearing the voices that came from it more so than anything else. This went on from early on in life through middle school. I didn’t have any friends whom I saw after school let out, and with the absence of my parents and my sister’s remaining in her room for the entirety of the day, I’d accept the images from the T.V. and movies as my company. And so I continued through life in a similar manner: a spectator that watched, engaged by what passed before me.

Along with the moving pictures, I found that my solitary play times provided much of my company. I knew the toys that I had at the time much longer than I knew many people. And so as I occupied those Saturday afternoons with my toys under the sunlight that shown through my window, I felt some semblance of kinship. It was the same way whenever I drew. Quite often, during and after class, between or during television shows, I drew. I drew what I saw on the television, extensions of story-lines from programs I watched, and scenes that I created in my head. I would only learn later on that it was my early need to tell stories and to be active in the stories I saw. From my solitude, I always wanted to connect with actual people through what I knew: stories.

Though horridly obese, and often dusty, the Panasonic acted as a very accommodating surrogate. If I didn’t like what I saw, it would change. If the voices were too loud, I could lower the volume. I even had a device to control these things remotely. My actual parents weren’t as understanding. In the early portion of my life, my father had a problem with alcohol. He often shouted after he drank, and he drank often. He cursed at my- more or less- 6 year old person, and every word he shouted fell down as punches. It could have been worse. But with what he wanted to release in himself, he succeeded in distancing me from him. There became a dense, unspoken air of fear, where I was afraid to speak lest I enrage him. And it was here that I really began to spend time in front of the television, quietly, seeing the backs of the people I lived with as they passed through the hallways to leave the house.

So, yes, socially, I began a little later in life than others. I had friends in school, but once 3 o’clock came around, I was suddenly the only boy in Yonkers. I believe that a personality is only truly formed in the midst of a bombardment with those around them; I didn’t have any sort of stronghold on who I was as an individual. That process came much, much later than it should have. But before that time, I wanted to be Urkel. I wanted to be Cory Matthews, Stone Cold Steve Austin, and the Fresh Prince of Bel Air. They are an eclectic group, but early in my life, they all kept me company. They were the performers and actors around whom the shows were based. I drew something from these images of people. I gave them a heart that beat behind their pixilated chests. And so with my admiration of their presence and bravado, they gained much greater weight than any image probably should have. But to me they were real, and I wanted to be like them. I wanted an applause of recognition when I entered the room. I wanted to be noticed and to have a tangible effect on people, whether it was joy or admiration, or, most notably, laughter.

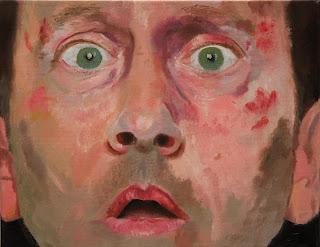

I began to try my hardest to make people in class laugh. I wasn’t as brave as Stone Cold Steve Austin, my favorite professional wrestler, but I could be an Urkel-esque sort of silly. And so, at the little six-desk island where we sat, I made faces at those in my immediate area and did imitations of the pointing face of Michael A., a student at the tables by the door who would cry to get Mrs. Gamboli’s attention but would be otherwise rude to the rest of us. I imitated people from the T.V. that we all knew, and relished in our shared knowledge.

Towards the end of elementary school, I began to take notice of the demeanor of the actors I watched, namely older men in film. It’s a weird thing. I said early that I wanted to be younger guys in sitcoms, like Ben Savage(Cory) and Will Smith (Fresh…), but it was more so the love that they received as characters, and the outgoing nature of their actions. And so through humor, I tried to fit in with the kids around me and as such gain the same sort of love. But although I vied for their attention through silliness, there was something about the quiet dignity and suave attitudes of the older actors. When I saw the Godfather for the first time, Marlon Brando’s performance changed my 8-year old feeling about myself. I was usually very reserved and quiet, save the moments I tried to get a laugh in the one-on-one situations. But when there were more eyes to scrutinize me, I spoke softer and used smaller gestures, speaking slower, thinking before I spoke. Seeing the reverence Brando received both on and off screen, I found that to be a viable option. I didn’t have to jump around to be liked. I didn’t have to stub my toe and fall down a flight of steps like Jaleel White (Urkel) to get people to laugh. I began to idolize the suave Sean Connery as James Bond- I can’t express how many times I’d cut my cheek trying to shave after a shower before I had any facial hair.

I never lost interest in what held my attention early in life. My passion for making people laugh manifested largely from my admiration for the characters whom I watched in lieu of having actual human contact. I wanted to tell stories and I wanted to be around people, to learn about myself through my interaction with them, and to engage in some sort of reciprocity.

Now in high school, I began to read short works of fiction, as well as longer prose. I began to write scenes that I would see in my head, situations for characters who materialized in my mind that spoke to me. For the lengthy periods of time that existed as voids during the day, I considered what I could talk about and what people would want to hear me say. I considered what I myself wanted to say and if I had anything to say at all. This is something that is still in the works. I wanted to tell the purest form of story: the truth. I took greater relish in the works of the classics which I now appreciate as the proper vehicles for this: Steinbeck, Fitzgerald, Salinger, Hughes, Twain, and whatever else the Yonkers Public Schools system privileged us.

I continued to draw. Now in my mid=teenage years, having never really pursued my artistic abilities, my talent caught up with my age. In Arnold M. Ludwig’s “Living Backwards,” Ludwig writes:

Even though your cultural mythology supplies you with the major elements and themes for your personal story, the story you eventually enter isn’t always clearly articulated.

So, I began to gravitate towards things that I felt were more acceptable, culturally- especially in the eyes of my parents. And for some time, I repressed my innate urge to express myself through my art, in lieu of engineering and mathematics. Growing up, I showed my mother pictures that I drew that I was particularly fond of. Although she showed some positivity towards drawings I did for projects, there wasn’t any encouragement in art as a whole. When I moved to show her words I had drawn on the side, she ignored them. The pressing issue for her, because, I believe, of the ‘cultural mythology’ that Ludwig speaks of, was mathematics and sciences. And so with my imposed priorities, my talents waned; I was no longer better than my age would suggest: something my teachers would tell me in elementary school. And so at the start of high school I drew less as a medium of connecting with things, and more as a novelty to make those around me laugh; I would, whenever I witnessed an injustice in class that involved my teacher shouting at a friend, draw a caricature of said teacher in a compromising position. Thankfully, I was never caught or, else the teacher’s indifference outweighed my cleverness, but, yes, I steered a bit away from my original authentic needs.

At the same time, during my early teenage years, I began to shift gears a bit in what I saw as a role model. I began to admire older actors, as I had, much more than I had. Namely because of their craft, which provides that they tell stories through their bodies. That is, they display emotions and attitudes and literally embody their passion. I began to see this as a great form of honesty, of truth- something that, to me, is very admirable. To depict scenes and to imbue scenarios and dialogues effectively, they must open themselves up, for good or ill, to the public. They must tap into something that is inside of them in order to reach something authentic for a role. And so with older actors, I saw a genuine mark of this. I saw a truth being told with their performances. And I saw within me the need to comment on things honestly, to be a story teller and to inform others of a perspective they would not have previously considered or been able to fathom, or even known existed. I also saw this with stand-up comedians.

Stand-up comedy, to me, has always been a very noble profession; for an individual to stand in front of an audience of strangers, essentially, and try to make them laugh- there are very few jobs that are as exposing for both parties. What the artist says to incite a laugh is the catalyst for this exposition. A laugh, much like a sneeze, is a gut-reaction, an instantaneous happening; to restrain it requires much energy. And so what a comedian says to tap into a certain area that lets this emotion and action loose tells much about not only the comedian’s prowess, but of what the audience member can laugh at. I have always felt a kinship towards comedians, having worked as a very, very low-level one for most of my life. And upon watching stand-up performances, I began to gauge whom I felt that kinship towards. And much as with the actors, with comedians it was whoever put themselves most in their act. Those who exposed their frailties and short-comings, those who held nothing back, and who spoke for the sake of honest discourse are whom I admired most. They are the comedians I admire deeply, as people. The first time I heard Richard Pryor talk about his life, and then saw Chris Rock and Louis C.K. and all of these great stand-ups talk about their lives openly, I sensed the greatest closeness for anyone that I had ever sensed. And I treasure their honesty as a discourse that is lost in our society.

The kinship I feel with these comedians and actors and writers seems to come from our similar pedigree. Though from different walks of life, and at different points in our respective lives, whatever we do comes from the same birth: the need to tell a story and to be heard. Whether on stage in front of strangers, or voiced through writing that is now held by someone who is now listening, or shown through a drawing or painting, the scripts that have informed my life have come from a lineage of individuals that have something to say and thirst for an audience to hear it.